Will O'Toole

May 1, 2020

The Phillies have scored just 37 times in 15 games this years (2.47 per game), tied with the Tampa Bay Rays for the fewest runs scored in baseball. Their .211 batting average is second-worst, their .269 on-base percentage is tied for worst, and their OPS of .614 is 26th.

The problem has been up and down the lineup, with the very top of the order the biggest problem. Players slotted in the lead-off spot have an on-base percentage of .145 and an OPS of .342 this season, both dead last in baseball. And don't get us started on the corner outfielders.

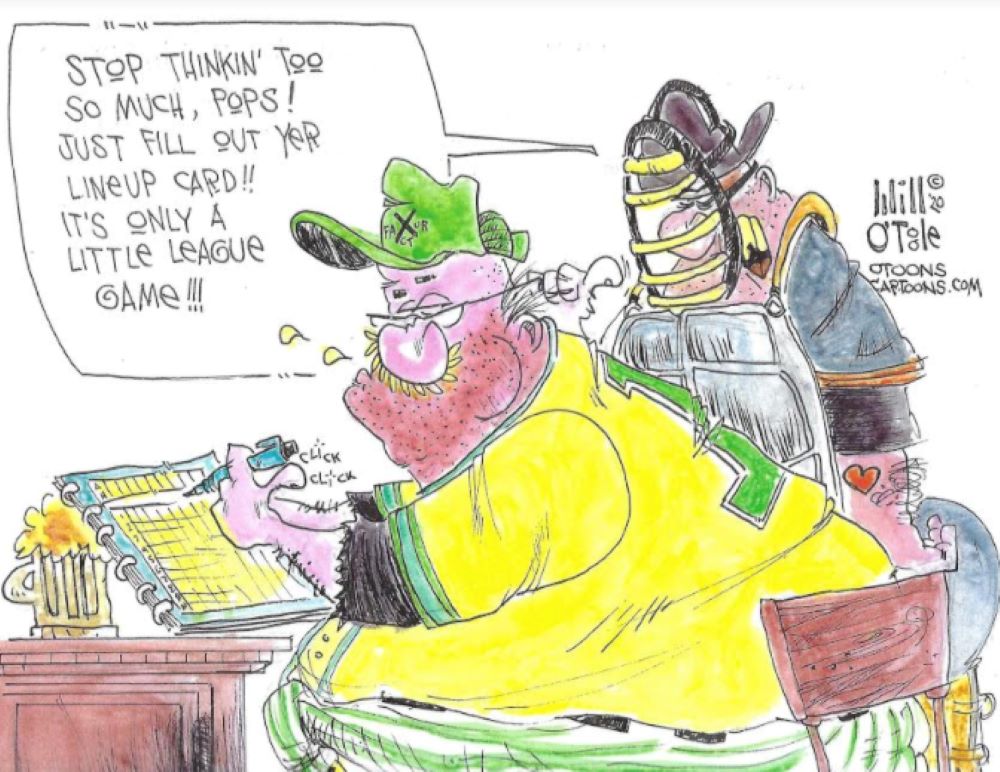

I must admit when I started this research I was looking for a connection between the lineup a manager pencils each of the 162 games and the offensive success of the team over the course of the season I know there have been studies and there probably are metrics and statistical analysis of the importance and impact of a lineup and its positive or negative affect on the individual team’s production.

And really each study is stereotyping hitters into an assumed mold or role.

The first player in the batting order is the leadoff hitter. Generally, the leadoff batter is the fastest baserunner on the team because he bats more often than anyone else in the lineup, and to have baserunners when the later, more powerful hitters come to bat, his need for a high on base percentage (OBP) exceeds that of the other lineup spots.

Brock was second to Torre in OBP. .421-.385 and led MLB with 126 runs scored. Understandably, Brock was a comet on the bases , Torre a rock. However, hitting them first and second or first and third in the order might have generated more offense and most certainly more at- bats for the team’s two best players.

The second hitter is most often just referred to as in the two-hole, is usually a contact hitter with the ability to bunt or get a hit. His main goal is to move the leadoff man into scoring position. Often, these hitters are fairly quick, competent baserunners and tend to avoid grounding into double plays.

Managers often like to have a left-handed hitter bat second, due to the envisioned, likely scenario of a gap in the infield defense caused by the first baseman holding the leadoff batter. is regarded as a table setter and has the ability to move the lead off hitter to the next available base.

The Cardinals number two hitters all year consisted mostly of Ted Sizemore, Julian Javier, Matty Alou (315) Luis Melendez, and Bob Burda. Collectively, they hit .279 /.352 OBP of an with 21 steals in 33 attempts (64%) and 16 sacrifices.

Not bad but if Schoendist kept Alou in the two hole the entire season, he would have had lefty contact hitter with little power but could hit behind Brock, setting up potentially a firs and third situation for Torre with no outs.

Oh right, Torre hit cleanup, not third. Even if Torre hit into a DP Brock would have scored on the routine 643 or 463 play.

The third batter, in the three-hole, is generally the best all-around hitter on the team, often hitting for a high batting average but not necessarily very fast. Part of his job is to help set the table for the cleanup hitter, and part of it is to help drive in baserunners himself. Third-place hitters are best known for "keeping the inning alive". However in recent years, some managers have tended to put their best slugger in this position.

The third hitter is seen as your best hitter today, not as much raw power as your slugging cleanup hitter, but enough to provide those three run homers that Earl Weaver preached. Given a first and third with Torre up would have allowed the MVP full throttle swings for the fences. Certainly, batting third would have given more opportunities for Torre to drive in runs even on terrible outs.

Ted Simmons, in his first full season behind the plate for the Cardinals, had the fourth most hits and the fourth most runs scored on the team hitting behind Torre. Imagine if Schoendienst had inserted the catcher in the three spot taking advantage of his switch hitting. The future hall of famer led the team with 10 sacrifice flies, ripped 32 doubles and knocked in 77 runs which were reasons why he finished in the top twenty for MVP.

Torre, was in the midst of his greatest season of his career banging out 230 hits still the most in the NL since 1969. He hit over 25% of the Cardinals’ homers and batted .363 with a ton of doubles with some splashes of triples in the extra base department.

Quite simply it was an MVP season.

Which he was awarded in the off season.

The Cardinals, a traditionally a competitive team, a franchise with the most World Championships finished behind the Pirates in the NL East.

Stargell had an unbelievable season too with major league leading 48 homers and 125 RBI and a splendid .295 average for a slugger hitting primarily in the fourth spot.

But Torre had 137 RBI to pace both loops on a team that scored forty fewer runs, one that didn’t have the power that the Bucs had. (95-154)

The Cards battled late into the year and pushed to within four games but it was never that close, as the race was really decided in June when the Redbirds lost 21 of 29 contests. The rest of the year was cosmetic. It was the Bucs year , a rare occurrence in the NL except for the early years of the 20th century. In fact, the Pirates’ 97 wins were the franchise’s most since the 1909 Pittsburgh team totaled 110 victories in a 154 game schedule.

The Pirates were buoyed by an offense that led the NL with 788 runs almost a full run above the league average 655. They led in homers, hits and triples.

They could pound the ball and run the bases and pound the ball even more.

The Cards? Well, they finished first in steals, batting average and on base pct.

The Cards had a good season, but the Pirates had one of their best in their history. Take away the abysmal June and the Cards played .622 ball.

Legitimately, if they had played just one game above .500 they tie Pittsburgh.

But IF doesn’t count.

However, if you applied today’s metrics to seasons past, could 1971 have ended differently?

Red Schoendienst and Danny Murtaugh were regarded as knowledgeable managers. The players seemed to like them, enjoyed playing for them, no real disputes or controversies. But did the get the best from their respective offenses?

Baseball “experts” would never confuse them for Dick Williams, Walter Alston, Billy Martin, Sparky Anderson or Earl Weaver.

Murtaugh’s response would be to hold up his 1960 AND 1971 World Series rings. Schoendienst won two pennants and the 1967 Series.

Fair enough.

But when you look at the Pittsburgh box scores 49 goose eggs are laid in the first inning . The study is not comprehensive but compared to the Cardinals and one realizes that St. Louis, for a team that finished second in the league in scoring with 739 put up 63 zeroes in the initial frame.

One would think that a winning baseball team would have a “ton o’ runs” in the first inning but the Pirates put up a crooked number in fewer of a third of their games. They started their championship season going scoreless in 11 of their first 12 games. The longest consecutive streak of first frame runs occurred, ironically, in June when they distanced themselves from the Cards. They tallied runs in six straight games. Finally, a fan might think, Murtaugh went against conventional strategy inserting an unconventional hitter in the two-spot. BUT no, he never replaced the Gene Clines, Richie Hebners or Gene Alleys with an Al Oliver or even Roberto Clemente.

To be fair, Clemente was in and out of the lineup for the first half of the season, pestered by minor injuries, aches and pains to his 36 year old body.

Stargell?

He spent time in the sixth slot against some tough lefties and really never cemented the cleanup spot bouncing around in the occasional third fifth as well.

Somehow the Pirates, who put up the white flag instead of the Jolly Roger and surrendered the first inning for two thirds of the season, continued to win.

Red?

With the exception of two games he rested the MVP, Torre hit cleanup in every game And Torre hit and hit and hit.

Which may be the reason I think Red may have blown a chance to win the division.

Torre hit .363 for the season but as the leadoff man in the second inning he hit 365 (23/63) and leading off any inning he hit .331 (53/160).

Had Red moved him or slotted newcomer switch hitter Ted Simmons in the number three spot or even number two and Torre third, one wonders if with the extra at bats if the Cardinals could have been more victorious. Winning 90 is an accomplishment, playing .622 ball outside of June is impressive. Did Schoendienst do everything possible to inject more juice into his offense by altering the lineup or opposing conventional wisdom?

Two slow catchers hitting two and three in the order?

Unheard of!

What’s Red thinking? Why not?

Torre in June showed no let up, no slump.

Consider:

With no one out, Torre hit .484 slamming 30 hits in 62 at-bats.

After the Cards went down 1,2,3 in the first, he was 23 for 63 leading off the second inning, with a homer for a .365 average.

As a leadoff batter in any inning he was 53/160 for a .331 average.

With two outs Torre walloped 76 hits in 212 at bats with five homers for a .358 average.

Torre with one out hit .357 71/199.

It was a magical season for Torre one he would never repeat.

Torre grounded into 16 double plays but none with the bases loaded?

Why?

Because the Cardinals offense gave him only seven opportunities all year with “ all the ducks on the pond.”

Torre, in typical MVP fashion, went 5 for 6 with a BB and oddly, two triples and 12 RBI.

But no homers.

So, did the Cardinals take full advantage of his greatest season? Did they invest enough in his at-bats and realize the most from batting him fourth.

Or could Red have gone against conventional wisdom and done something radical?

Does the positioning of your hitters have a discernable impact on the team’s overall run production or is it really just a crapshoot?